The archaeological island of Delos exists as a unique territory in the Aegean Sea, a place where human birth and death were legally prohibited for centuries. The Athenian decree of 426 BC established this absolute purification, ordering the removal of every grave to the neighboring islet of Rhenia. The island was to remain untouched by mortal transition so that the Sanctuary of Apollo could exist in a state of ritual clarity.

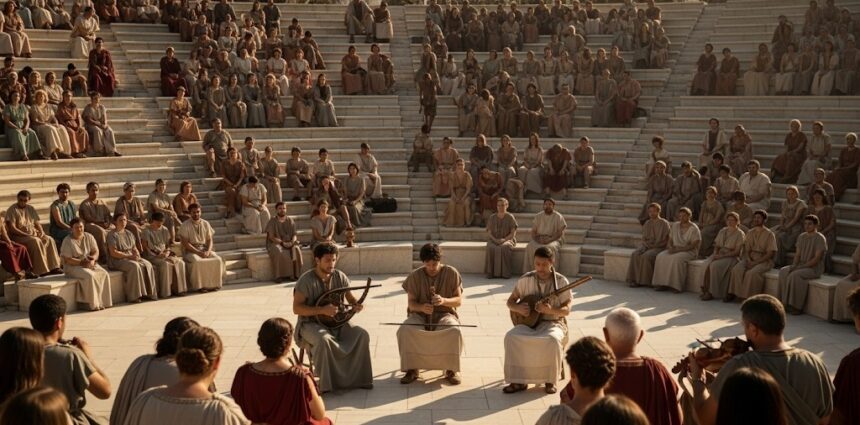

Delos served as the religious center of the Cyclades during the Archaic and Classical periods, later transforming into a massive tax‑free commercial port under Roman rule. UNESCO designated the entire island a World Heritage Site in 1990 for its remarkably preserved Hellenistic urban layout, its sanctuaries, and its monumental architecture. Excavations by the French School of Athens since 1873 have revealed nine temples, a theatre for 5,500 spectators, and the iconic Terrace of the Lions. Today, Delos remains uninhabited to preserve its status as an archaeological reserve — a silent island under divine law.

Rituals — The Decree of Absolute Purity

The purification of 426 BC was a geopolitical maneuver disguised as piety. Athens, weakened by plague and war, sought Apollo’s favor through a radical act: the total cleansing of the god’s birthplace.

Every grave was opened. Bones and offerings were packed into crates and ferried across the narrow channel to Rhenia. The state then issued a permanent ban: no one could be born or die on Delos.

Pregnant women were relocated weeks before their due date. The dying were carried to boats before their final breath. No blood could touch the soil of the sanctuary.

This created a curated reality, a city of the living that refused the body. Delos became a stage for the divine — a territory where human biology was suspended in service of cosmic order. Athenian triremes patrolled the boundary, and the Delia festival celebrated this new ritual architecture of purity.

Structures — The Lions, the Temples, and the Engineered City

The Architectural Guardians of the Sacred Lake

The Terrace of the Lions, carved from Naxian marble in the late 7th century BC, forms the eastern border of the sacred precinct. Their open mouths face the rising sun, guarding the Sacred Lake where Leto was said to have given birth to Apollo.

The lake, drained in the early 20th century to prevent malaria, is now a dry basin where reeds whisper in the wind. The absence of water changed the acoustics of the site — a shift in the island’s sonic memory.

The path between the lions leads to the Sanctuary of Apollo, containing three temples. The Great Temple of the Delians, a peripteral Doric structure, still stands with unfluted columns — smooth cylinders of marble that record the economic interruptions of the era.

The Commercial Zenith of the Free Port

In 167 BC, Rome declared Delos a free port to undermine Rhodes. The island became the busiest commercial hub in the eastern Mediterranean, its population surging to 30,000. The Agora of the Italians was the center of this world, where ancient records describe slave auctions of staggering scale — up to 10,000 people in a single day.

Because Delos had no natural resources, survival depended on engineering. Houses contained elaborate cisterns, such as the granite‑arched system beneath the House of the Trident, which still holds rainwater after two millennia. The city relied entirely on the sky and the sea.

Mount Kynthos and the Prehistoric Memory

Mount Kynthos, rising 112 meters above the Aegean, offers a panoramic map of the Cyclades. Its summit preserves traces of a prehistoric settlement from the 3rd millennium BC — a reminder that Delos was sacred long before Apollo.

The Kynthos Cave, reinforced with massive granite slabs, was constructed in the Hellenistic period to appear ancient. It is architecture masquerading as prehistory — a deliberate invocation of older forces.

Descending the mountain, one passes the Sanctuary of the Syrian Gods and the Heraion, where the wind is strongest and the stones seem to vibrate under its pressure.

Echoes — Destruction, Abandonment, and the Long Silence

Delos reached its zenith quickly and fell just as fast. In 88 BC, Mithridates VI of Pontus attacked the island, massacring thousands and looting the sanctuary. A second raid in 69 BC completed the devastation. Trade routes shifted, and Delos became a ghost city.

By the 2nd century AD, the island was largely abandoned. Marble was quarried for nearby islands. Statues were burned for lime. Early Christians built small basilicas among the ruins, but even they eventually left.

For over a thousand years, only the lions remained.

Continuities — Winter Silence and the Future of Preservation

Winter reveals the true nature of Delos. The crowds vanish. The Aegean winds hum through broken pipes and empty cisterns. Grass covers the stones. The island feels alive in a way summer never allows.

The ancient decree — no birth, no death — is no longer law, yet it persists as a physical reality. No one is born on Delos. No one dies there. The cycle remains suspended.

Today, the threat is not war but rising sea levels. Parts of the Sacred Harbour are already submerged. Conservators battle salt crystallization, washing marble with distilled water to slow its decay.

The island is now entering a new phase of preservation. Every stone is being mapped. Every mosaic photographed in high resolution. Ground‑penetrating radar and 3D modeling are creating a detailed record of the site — a way to ensure that the memory of Delos endures even if the sea continues to rise.

This is the new form of care: to protect the fragile with attention, precision, and continuity.

The island remains. The wind remains. The god remains.